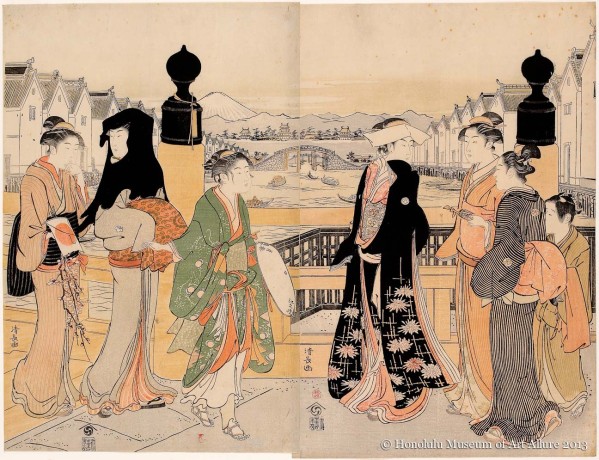

Even before the chōnin (townspeople) reached their height of influence during the 18th century, the subjects portrayed by artists had expanded to include contemporary customs (fūzoku), resulting in the popularity of what has commonly been called by modern art historians “genre painting” (fūzokuga) starting a little more than a century earlier. At this point, patronage of the arts still was mainly limited to the upper classes, in particular the warriors (bushi ) from which the elite rulers of the time emerged. However, in addition to orthodox paintings of classical landscapes and historical and religious subjects, painters also began to depict scenes of leisure (parties), seasonal festivals (such as cherry blossom viewing), theatrical performances, and brothels.

At the same time, it was not until the widespread availability of printing technologies and the diffusion of popular publishing houses in the mid-Edo period that the audience expanded to common people through the “art of the floating world.” While the fabled Yoshiwara and its courtesans became increasingly important subjects, other aspects of fūzokuga were also absorbed into ukiyo-e, allowing us a fascinating window into daily life—at least as artists interpreted it—more than two centuries ago. The conception of beauty in ukiyo-e was by no means limited to the pleasure quarters, and artists such as Kiyonaga and Utamaro turned their attention equally to street scenes, outings to popular recreational areas, and even family relationships.