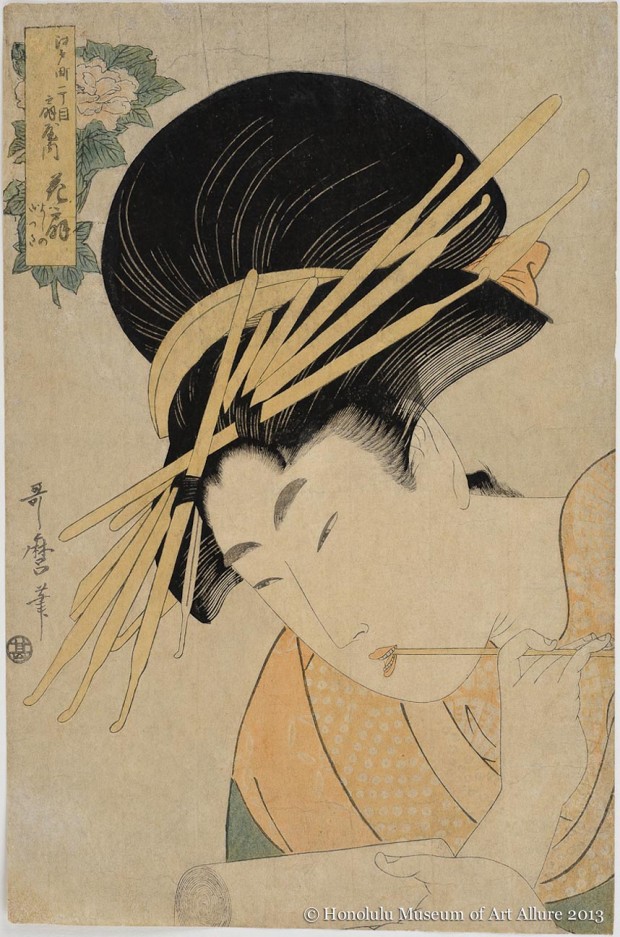

Following the model of Shimabara in Kyoto, the new urban political center of Edo established a single licensed district for brothels, the Yoshiwara, in 1617-1618 (later moved to its permanent location in 1656-1657). The initiative for the Yoshiwara seems to have come less from an intention on the part of the government to limit prostitution, than from the brothel owners themselves, in an attempt to establish a lucrative monopoly. Early on, these businessmen realized that the Yoshiwara presented them with a unique opportunity to market not merely prostitution (which despite their best efforts, could be found in teahouses and bathhouses around the city), but instead a distinctive culture of fashion and sophistication that perfectly manifested the rapidly changing society of their time. No doubt with considerable encouragement from the brothel owners, the Yoshiwara soon captured the imagination of Edo’s writers and artists (who frequented the same circles, relied upon the same publishers, and regularly collaborated), and through them that of the chōnin: a legend was born.

The burden for maintaining this legend fell heavily on the Yoshiwara’s courtesans, many of whom had been sold into the brothels as adolescents. Through the brothels, a successful courtesan acquired sophistication, material comfort, and above all fame (in rare cases allowing them to escape a rigid class structure, and marry into a family with wealth or even social status). On the other hand, aside from the fundamental fact that they were required to provide sexual favors for money (most of which went to the brothels), they were subject to rigid codes of behavior (for example, never eating in front of a client), under constant scrutiny for the slightest faux pas that could damage their reputation, and pressured with financial obligations that, in the worst cases, could keep them in a state of constant indebtedness little different than slavery.